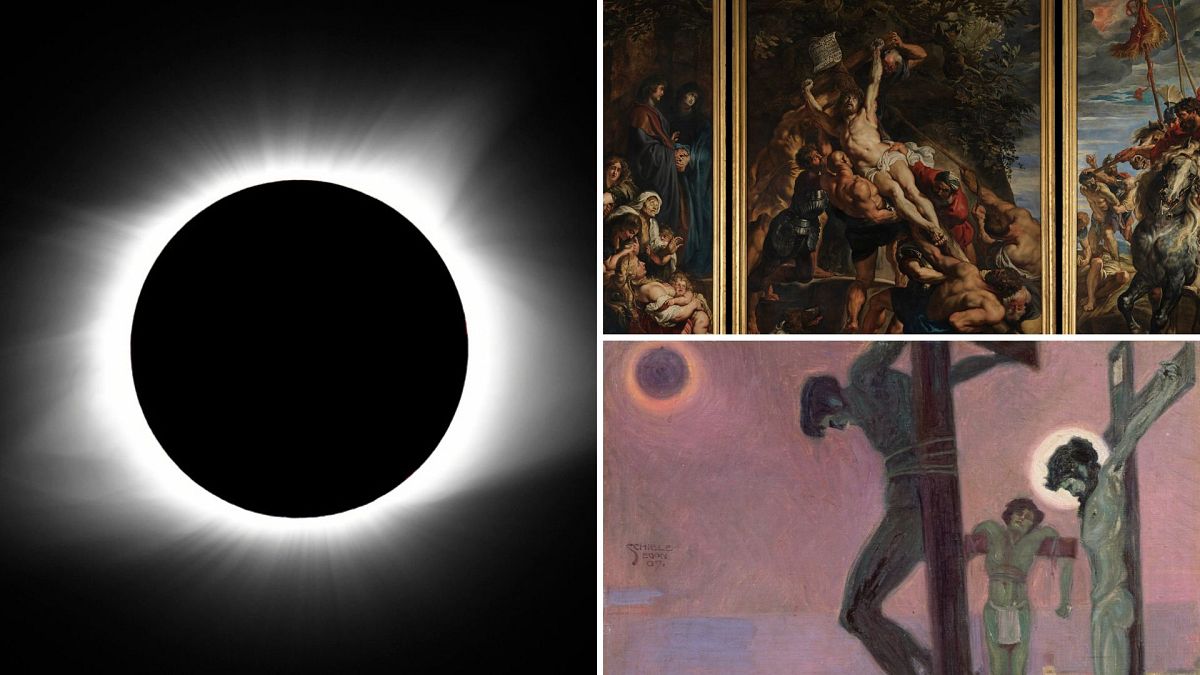

Total eclipse of the art: How the disappearing sun has long captivated the creative imagination

The upcoming 8 April total solar eclipse, which for a few minutes will appear to many North Americans to have extinguished the sun, is already casting a wide shadow. A quarter of US citizens are expected to journey to various locations where the eclipse can be seen at its most complete – not to mention […]

The upcoming 8 April total solar eclipse, which for a few minutes will appear to many North Americans to have extinguished the sun, is already casting a wide shadow.

A quarter of US citizens are expected to journey to various locations where the eclipse can be seen at its most complete – not to mention the legions of skygazers planning to travel in from abroad.

But why is this event, which will happen again in 2044, getting so much attention, with live coverage already confirmed across popular news and streaming platforms for those who can’t make the trip?

Well, aside from taking place in a part of the world known for its ability to promote almost any event so long as it can turn a buck, a brief look at how eclipses have featured in art and literature might give some clue as to why this particular event is enrapturing public imagination.

Artistic depictions through the ages

From ancient Egypt onwards, eclipses have almost always been viewed as bad omens. For this early civilisation, if the sun was suddenly stolen from the sky then some evil business was taking place among the gods.

Day and night, sun and moon – these things are meant to stay separate. Otherwise, trouble is brewing.

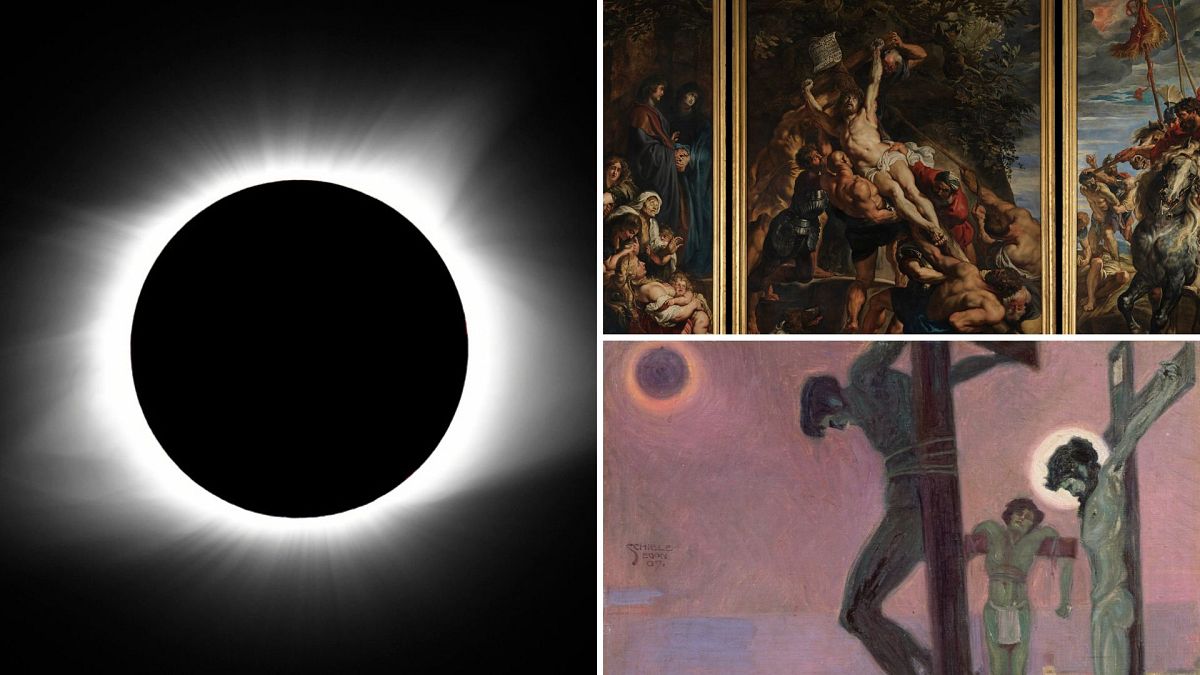

Not for nothing did Renaissance painters such as Rubens include eclipses in depictions of Christ’s crucifixion, a symbol of hope being blotted out by darkness.

The Austrian expressionist painter Egon Schiele made a point of referencing this trope in his 1907 painting “Crucifixion with Darkened Sun”, where the only light in the scene emanates from a ghostly second sun: Christ’s halo.

By the early modern period, the idea of eclipses spelling bad news started to flesh itself out as more of a political than religious omen.

The cycles of day and night and light and dark came to be associated with the cycles of politics.

In Shakespeare’s 1605 tragedy “King Lear”, Gloucester observes: ‘These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us.’

Half a century later, John Milton wrote in “Paradise Lost” that the sun:

It’s not difficult to see from that one why, in a year when nearly half the global population will be going to the polls, many of them threatening to elect alarming ‘change’ candidates, this upcoming eclipse might be speaking more than ever to our uneasy world.

Nor is it difficult to to imagine that this time around we might see a repeat of scenes like those described by diarist John Evelyn, in 1652, of a solar eclipse which “had so exceedingly alarm’d the whole Nation, so as hardly any would worke, none stir out of their houses; so ridiculously were they abused by knavish and ignorant star-gazers.”

But strong as the potential is at the moment for doom and gloom, it doesn’t have to be that way.

Eclipses have been depicted in many different ways by artists in the past few hundred years, not all of them grimly portentous.

Emily Dickinson, for instance, has a lovely untitled poem whose first stanza reads:

More recently, eclipses have of course been heavily featured across popular culture, from Stephen King to Stephenie Meyer, Avatar: the Last Airbender to Avatar: The Way of Water.

And perhaps the stats will confirm that for the most part these disruptive phenomena are still seen as ill omens. But in the best art there is always light stealing out from behind the dark.

Virginia Woolf, experiencing a solar eclipse in 1927, describes in her diary the initial plunge into darkness: “Suddenly the light went out. We had fallen. It was extinct. The earth was dead.”

But then, just as the terror of the moment grips the gathered skygazers, the colour comes back: “At first with a miraculous glittering and ethereality, later normally almost, but with a great sense of relief. It was like a recovery.”

Because what’s important to remember with all these eclipses, real or fictional, is that the darkness they bring is fleeting: it will pass.