‘Despite rice fund, productivity remains low’

Special report (Second of three parts) MANILA, Philippines — Nearly P80 billion and counting. That’s the amount of money, primarily tariffs, collected from rice, that the government has plowed back to the local rice industry since the creation of the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) in 2019. RCEF is a six-year fund meant to make […]

Special report

(Second of three parts)

MANILA, Philippines — Nearly P80 billion and counting.

That’s the amount of money, primarily tariffs, collected from rice, that the government has plowed back to the local rice industry since the creation of the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) in 2019.

RCEF is a six-year fund meant to make rice farmers competitive.

It now amounts to P79.336 billion at the end of 2023, based on the computations of The STAR.

The amount includes the guaranteed annual P10 billion allocation as well as the rice tariffs collected by the Bureau of Customs in excess of P10 billion.

From 2019 to 2023, the government earmarked P29.336 billion in excess rice tariffs for the rice industry, providing P5,000 cash assistance to every farmer tilling two hectares of land and below.

Government documents obtained by The STAR showed that the Department of Agriculture allocated P28.211 billion for cash assistance distribution under the Rice Farmers Financial Assistance (RFFA) program.

As of Feb. 19, the DA has distributed P20.456 billion in cash assistance, with over P6.3 billion remaining to be credited to farmers this year.

This year marks the sixth and final year of the RCEF or the rice fund with a total budget expected to reach a record level of P30 billion (P10 billion from the guaranteed fund and P20 billion from last year’s excess rice tariffs).

That would bring the total RCEF investment by the government over the six-year period to a whopping amount of nearly P110 billion, enough to bankroll a year of Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program implementation.

Where’s the growth?

Despite the billions of investments through RCEF, some industry stakeholders and experts are dismayed that its impact on local rice productivity was slower than expected.

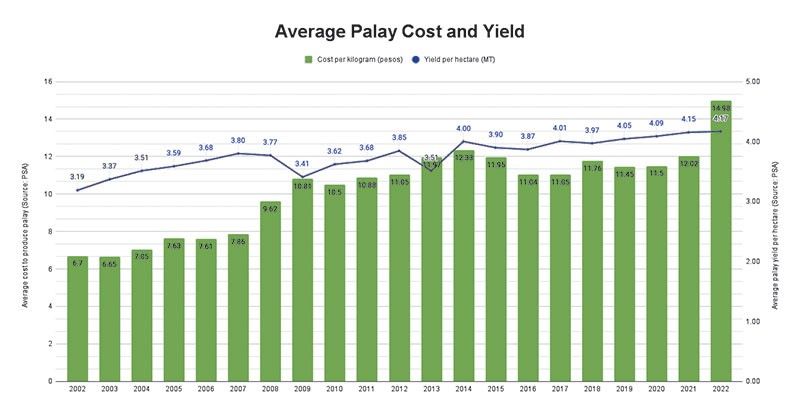

The national average yield per hectare at the end of 2023 stood at 4.17 metric tons (MT), about five percent higher than the 3.99 MT posted in 2018 prior to RCEF implementation. This meant that rice farmers increased their production by 180 kilograms for every hectare they planted last year.

This growth, however, is far from what the RCEF envisioned, which was to hit at least 5 MT per hectare, says Raul Montemayor of Federation of Free Farmers.

Senen Reyes, the executive director of the Center for Food and Agri Business of the University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P-CFA), shared the same sentiment: RCEF did not even reach the bare minimum.

“It did not inch that much to the point that we want to happen. At the bare minimum, it should have been 4.5 MT,” Reyes told The STAR.

But for Monetary Board member V. Bruce Tolentino, RCEF was a success — just look at the record palay harvest last year of 20.06 million metric tons.

“To me that is explained essentially by the [RCEF] seed program implemented by PhilRice,” Tolentino, a former agriculture undersecretary, told The STAR.

Tolentino said the increase in national average yield is already “good” considering the performance of the industry in the past decades. He noted that yields in the RCEF priority areas are above the national average.

PhilRice or the Philippine Rice Research Institute revealed that 13 provinces have already posted an average yield of more than five metric tons per hectare and 15 provinces have an average yield of between 4 and 5 MT, since RCEF began.

External factors intervened

If the cost to produce a kilogram of palay would be the barometer for RCEF’s success, one might think twice.

Palay production cost, in nominal terms, in 2022 averaged to an all-time high of P14.98 per kilogram, P3.22 more expensive compared to 2018, based on Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) data.

Meanwhile, average net returns of rice farmers, or the profit they get after deducting their total expenses to their gross revenues, fell to a decade-low of P17,305 per hectare, according to PSA data.

But experts say that these figures should be taken with a grain of salt given the unforeseen external circumstances that coincided with the RCEF implementation: COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war.

These two events distorted the global trade landscape and affected all food producers, including Filipino rice farmers. The skyrocketing of fertilizer prices in 2022 is a testament to this.

“You have to look at the accomplishments of RCEF in its pilot areas. You may not see its overall impact at the national level but it may have made great strides in its implementing sites,” Ditas Macabasco, a senior agribusiness specialist at UA&P-CFA said.

“These external factors, including climate change even, could have offset the gains from interventions of RCEF,” she added.

Tolentino said that the production costs of palay must be assessed in terms of real terms, which exclude inflation and other market factors, to determine the real impact of RCEF.

To extend or not to extend?

It is up to the Congressional Oversight Committee on Agricultural and Fisheries Modernization or COCAFM to determine whether RCEF was a success or a failure. And in that determination lies the future of the fund – to extend or not to extend?

The COCAFM is expected to meet this year to evaluate the achievements of RCEF.

Industry sources told The STAR that legislators will have to race against time if they want to extend the RCEF since the activities for the 2025 midterm elections are drawing near.

Agriculture experts and industry players want to extend RCEF but they are divided on how long it should be. Some are saying that it should be “indefinitely” until rice farmers become competitive while others propose a six-year extension.

Regardless, they all agree that the RCEF allocation must be revisited, which was mandated by law but was not done by the government as it was overtaken by events, particularly COVID-19 pandemic.

Leverage some flexibility

Legislators must consider providing a room for “flexibility” in terms of allocating the RCEF, unlike its current state of predetermined albeit “rigid” allocation.

Fermin Adriano, an economist and a former agriculture undersecretary, proposed that RCEF’s components must be determined at the regional or even at the provincial level to cater to the varying needs of farmers nationwide.

Region III, for instance, needs most post-harvest facilities while Regions VI and VIII would require more seeds and fertilizers to boost their respective rice productivity, Adriano said.

Philippine Chamber of Agriculture and Food Inc. president Danilo Fausto proposed that the RCEF must still have a fixed budget but its allocation must be determined during the annual budget deliberations to take into consideration the needs of farmers in every region.

He said billions of funds were unutilized at the start of RCEF because implementing agencies were overwhelmed with the money channeled to them.

If certain agencies are underperforming, their allocations must be revisited immediately in the following year to ensure timely use of funds, he said.

Monetary Board’s Tolentino concludes:

“I believe it is high time for the legislature and the DA to agree beforehand on what parameters should be. I agree that there should be some parameters so that the budget is clearer and it will facilitate accountability.”

(To be concluded)