Preserving cultural history amid urban growth

Preserving cultural history amid urban growth

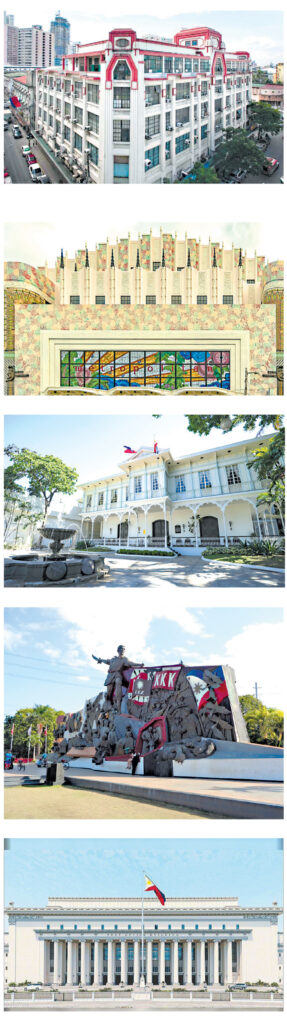

Metro Manila’s urban identity is often associated with its density, skyline, and the relentless churn of new developments. Within this region, the City of Manila, as one of the most populous urban areas in the world, is a bustling hub of trade and commerce, but one inarguably possessed of an old-world soul.

Based on numbers alone, from the data gathered by the City of Manila, the district of Sta. Ana has the most heritage sites in the country with 88, followed by the districts of San Nicolas and Malate with 78 and 55, respectively.

Under the Philippine Registry of Heritage, formerly known as the Philippine Registry of Cultural Property or PRECUP, cultural properties are categorized into several types based on how they are recognized and declared.

Cultural properties included in this registry fall under several formal classifications, each carrying distinct legal protections and historical significance, as determined by national and local cultural agencies.

At the highest level of designation are National Cultural Treasures, which are unique cultural properties found within the Philippines that possess outstanding historical, cultural, artistic, or scientific value. Also of national importance are Important Cultural Properties, which refer to cultural properties recognized for their exceptional cultural, artistic, and historical significance to the country.

Under the purview of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines are additional heritage classifications, including National Historical Shrines, which are hallowed sites revered for their deep historical and often sacred associations; National Historical Landmarks, which are places or structures directly associated with significant historical events or achievements; and National Historical Monuments, which are physical commemorations of important historical figures or moments.

At the international level, UNESCO World Heritage Sites are cultural or natural properties located in the Philippines that have been inscribed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization for their outstanding universal value to humanity.

Apart from formally declared properties, the law also recognizes a broader group known as Presumed Important Cultural Properties. These are cultural assets that have not been officially declared under any of the above categories but possess the essential characteristics of an Important Cultural Property.

Finally, there are Local Important Cultural Properties, which are identified and declared by local government units through their respective Sanggunian via ordinance, executive order, or resolution. These are properties of specific cultural, historical, or symbolic value to the local communities in which they are located, and their recognition plays a crucial role in strengthening local heritage protection and awareness.

Finally, there are Local Important Cultural Properties, which are identified and declared by local government units through their respective Sanggunian via ordinance, executive order, or resolution. These are properties of specific cultural, historical, or symbolic value to the local communities in which they are located, and their recognition plays a crucial role in strengthening local heritage protection and awareness.

Together, these classifications aim to preserve the Philippines’ rich and diverse cultural legacy, ensuring that historical memory and artistic achievement remain embedded within both national consciousness and local identity.

And Manila, a city older than the country itself, plays host to many of them.

Preservation as progress

The Philippines has a robust legal framework for cultural preservation. Republic Act 10066, or the National Cultural Heritage Act of 2009, mandates protection for structures at least 50 years old and classifies them as Important Cultural Properties (ICPs) or Heritage Houses.

Updates to this law, including RA 11961 passed in 2023, introduced a three-tier classification system for cultural properties, allowing tailored conservation standards for Grades I to III.

Despite this, legal protection often lacks teeth. There have been plenty of reports over the years that have pointed out the law’s weak enforcement towards the preservation of Manila’s cultural heritage. Property owners frequently alter or demolish historically significant buildings without proper permits or oversight, such as the Sta. Cruz building in Escolta that was demolished surreptitiously amid the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, or the demolition of the Sanchez House on Bilibid Viejo Street in Quiapo.

Such events have been the source of countless controversies about Philippine heritage, and yet what’s often missing from the debate is this: heritage need not be an obstacle to urban development. In fact, it can be a catalyst for sustainable growth.

A recent Asia-Pacific study using Manila as a case study found that integrating heritage into urban planning can boost local tourism, community resilience, and economic diversity.

A recent Asia-Pacific study using Manila as a case study found that integrating heritage into urban planning can boost local tourism, community resilience, and economic diversity.

The study, titled “Sustainable Cities in Developing Countries: A Case of Balancing Cultural Heritage Preservation and Tourism in Manila, Philippines” and published in the Asia-Pacific Social Science Review, found that cities that balance conservation with modernization like Kyoto, George Town, or Singapore’s Chinatown demonstrate that “a sustainable urban revitalization program can effectively promote a creative economy that can generate employment opportunities and improve the existing economic conditions, especially for low-income citizens who are part of the city’s humanscape.”

In Manila, this is already happening in pockets. The Goldenberg Mansion in Malacañang complex, a Moorish-revival home built in the 1870s, was recently restored and reopened as a cultural center in 2023. Escolta’s First United Building has been repurposed into a creative hub for local entrepreneurs.

Grassroots movements are also gaining momentum. Organizations like Renacimiento Manila are spearheading public campaigns, walking tours, and digital awareness drives to build civic pride and policy pressure.

Manila today stands at a crossroads between its storied past and its visions of the future. One prioritizes verticality, volume, and economic scale; the other values continuity, character, and cultural capital.

But these visions need not be mutually exclusive. Preserving heritage does not mean freezing the city in amber. The numerous heritage sites in the city prove that Manila is a living vessel of collective memory. And what is a nation but a shared memory? — Bjorn Biel M. Beltran

With Beyoncé's Grammy Wins, Black Women in Country Are Finally Getting Their Due

February 17, 2025

Comments 0